Since September, the Chinese SECM and French CNES teams have been working together on the integration and environmental testing of the “qualification model” satellite. This satellite model is used to verify that all its components fit together correctly and that the assembly will be able to withstand the mechanical, thermal and electrical environments encountered during launch and life in orbit. It is also a kind of practice run of the activity that will be carried out on the “real” flight model satellite, a rehearsal during which both the procedures and the joint operation of the teams are tested. It should be noted that, although it is not the “real” satellite model at this stage, nor the real instrument models, these are accurate models designed to validate the overall mechanical, thermal and electrical behaviour.

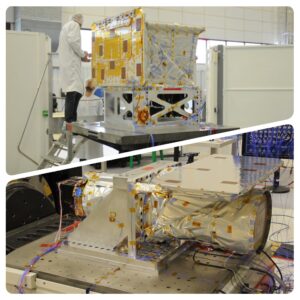

For the French teams it started out with the integration of the ECLAIRs and MXT telescopes on the satellite. This is the moment when we check that what works in theory on a computer also works in real life. Like a Tetris, everything has to fit together correctly and the holes have to fall in front of the holes. The dexterity of the integration teams is heavily tested as the space available is limited and the screws to be tightened are not easily accessible. Nerves are severely strained, and everyone gives a big sigh of relief when everything falls into place and snaps into place.

Then it’s time to power up the satellite, check that everything is working and that the various instruments and subsystems are communicating with each other. The electrical and command/control teams take over from the mechanics to play out test sequences representative of the life of the instruments and satellite throughout the mission. Several tests of this type have already been carried out, so this phase is of little concern, but it is still a great satisfaction to see that everything is going normally.

After one month of operation, the satellite is now ready for environmental testing:

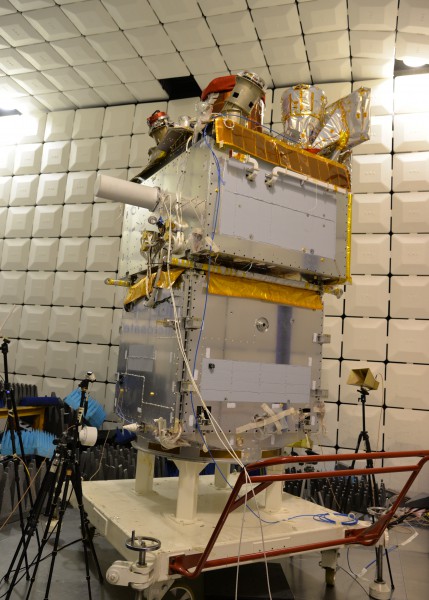

- First, electrical tests known as auto-compatibility. The aim is to check that electrical disturbances produced by one piece of equipment do not interfere with the operation of the others, in other words, to test that “electrical” cohabitation goes well. For the French instruments, which are not at all representative in terms of performance, the aim is above all to gain a better understanding of the environment and the sources of disturbance to be encountered in flight.

- This is followed by thermal tests during which the satellite is installed in a vacuum chamber that simulates a vacuum in space and undergoes several temperature cycles between the “cold case” and the “hot case” satellite. These tests, carried out continuously over several days, involve 3 x 8 operation of the teams. The predictions made prior to the tests predict temperatures for our instruments to be at their coldest around -70°C and at their warmest up to +40°C. While the primary objective is to verify that the instruments operate at such temperatures, it is also an opportunity to validate the temperature predictions and the thermal models that go with them. Finally, at the end of 3 weeks under vacuum, everyone holds their breath when the tank is opened and sees that the satellite has not suffered any degradation. Fortunately, everything is fine, so the tests can continue.

- The last test sequence is certainly the most impressive as it involves shaking the satellite in all directions to check that everything holds together. The sequence takes place in 3 stages. First, the satellite, just like the instruments before it, is installed on a vibrating pot. It will be shaken, axis after axis, according to a sinusoidal movement whose frequency, between a few hertz and 2000 Hz, and amplitude will be progressively varied.

- Then the satellite is placed in an acoustic chamber. This is to reproduce the noise, using a set of giant trumpets, to which the satellite will be exposed during launch. Our ears would not resist it, but the satellite passes the test with ease.

- Finally, it is time to check that the satellite can withstand the shocks associated with the deployment of the solar panels, when the screws holding them folded back on the satellite are cut by explosives. And there’s really nothing more efficient than deploying a solar panel in real size, which allows to check that the deployment is working properly.

After 5 months of activity in China, the satellite and its instruments passed all the tests to which they were subjected with success. It’s time to take a break, and for the French teams who have been taking turns since the beginning of September to take a rest. The next appointment is set for early February with the Chinese teams for final electrical tests. Unfortunately, current events in China have decided otherwise, forcing us to delay this final sequence. But that’s only a postponement.